Have you ever had a gut feeling about someone or something that you wish you hadn’t ignored? This may have been accompanied by a physical sensation of tension, agitation, a sinking feeling, constriction, or aversion—your body was letting you know that something was off, but you disregarded it. I recall a handful of these events—once when I handed my credit card over to an agent promoting a timeshare vacation in Mexico, another when a new acquaintance asked if he could borrow some money, and a third when a friend shared some health symptoms and was later diagnosed with cancer. In each case, the gut feeling was correct, conveying risk, threat, or danger, yet some mechanism in me chose to override it.

I can now name the mechanism in each case as being: 1) a tendency to appease; 2) a desire to be ‘nice’; 3) pretending that everything is OK when it isn’t. Each of these is a coping strategy I utilized in childhood to adapt to my environment and maintain the connection and approval of family, teachers, and peers. These mental patterns talked me out of my gut feelings and can still show up. Perhaps you can identify the same or other coping strategies that disconnect you from your gut feelings.

We also have positive gut feelings registering as excitement, warmth, openness, joy, ease, or expansion that let us know that something remarkable is happening—perhaps on a first meeting with someone who will become important in your life, or the recognition that you are meant to travel to a particular destination or take a specific course, or a sense when you walk into a building or outdoor space that the sacred lives there. I had this experience when I “felt” my daughter was pregnant before she knew herself. When I asked her, she said she wasn’t. She confirmed that she was pregnant a week later after a pregnancy test. With pleasant gut feelings your body is pulled towards something with a calm alertness and inner buoyancy. Curiosity opens, attention heightens, presence expands, and joy flutters.

Gut feelings can help us recognize when something is right and in alignment or when it is not. With time, awareness, repetition, and familiarity, we can learn to listen to and decode the body’s signals and trust them.

What are Gut Feelings?

Gut feelings are an internal response to external reality designed to protect us from danger or threat and to recognize when safety is present. They help us to survive and form part of our embodied intelligence. They are rapid, body-based perceptions that arise from the gut, heart, viscera, and body without conscious reasoning but are informed by deep physiological and neurological processes. When we pay attention to gut or visceral feelings and other sensations, our body, nervous system, and brain work together to signal either safety, danger, opportunity, connection, excitement, or what is true and right for us before the rational mind steps in to analyze, compensate, disagree, or talk us out of or into something.

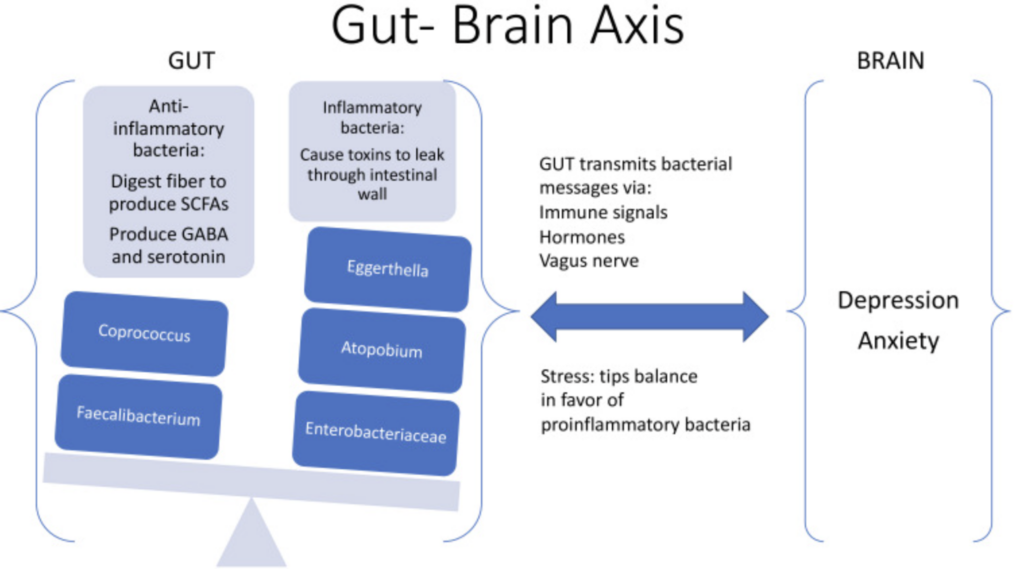

They originate as physical sensations primarily in the gut, home to the enteric nervous system, also known as the ‘second brain.’ The enteric nervous system is comprised of a network of over 500 million neurons embedded in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, which can work independently from the brain and spinal cord. The heart also has its own little brain, composed of between 14,000 – 40,000 neurons. (The entire brain contains 86 billion neurons while the spinal cord contains 69 million neurons). The enteric nervous system regulates digestion, peristalsis, secretion of enzymes and mucus, absorption, and excretion. It connects to the brain via a bidirectional highway, known as the gut-brain axis, whose main thoroughfare is the vagus nerve. The vagus relays information from the internal organs to the brainstem and other brain regions involved with feeling expressing, and interpreting emotions, including the amygdala, hippocampus, insula, anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex. Thus, the gut-brain axis links both emotional and cognitive areas of the brain with the gut through a two-way communication system.

Your gut is always talking to you—receptors in the gut respond to sensations of tension, fullness, pressure, ease, contraction, and inflammation, as well as to hormones and the composition of gut bacteria and their metabolites. Information from these receptors is carried to the brain via the vagus nerve to affect emotions, mood, mental clarity, and decision-making. An imbalance in your gut bacteria can also contribute to an impaired immune system, heart disease, diabetes, digestive issues, allergies, arthritis, neurological symptoms, cancer, and various forms of inflammation. Many conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, major depressive disorder, obesity, type 2 diabetes , and colorectal cancer have a consistent gut microbiome “signature” with an increase in certain gut microorganisms and a decrease in others.

An increased diversity of organisms in the gut is a common feature of an optimal gut microbial community and overall well-being—the more the merrier. Gut bacteria ferment fiber to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, that act as an energy source for colon cells. SCFAs strengthen the gut lining, preventing toxins from leaking through the intestinal wall. They also regulate the immune system to decrease inflammation, improve our response to stress to enhance resilience, and increase brain plasticity and myelination to augment learning and brain function. Gut organisms participate in the development, improvement, and regulation of the immune system, endocrine system, and nervous system, as well as in the regulation of inflammation.

Surprisingly, the brain and mental states can generate changes in the gut environment and alter the composition of microorganisms, just as the gut microbiome can in turn influence mood and emotions. Trauma, persistent stress, and loneliness can alter the composition of the gut flora, resulting in the abundance of more gut organisms that trigger inflammation. Chronic stress can also affect the intestinal barrier, causing a ‘leaky gut’, which allows toxins produced by gut microorganisms to enter the systemic circulation and ultimately reach and negatively affect the brain.

Diagram is open access from Gen Psychiatr. 2023 Feb 17;36(1):e100973.

To some extent, our mood is programmed by the microscopic orchestra of organisms in our gut. We have approximately an equal number of bacteria in the gut as we have cells in the body—about 38 trillion. Within that massive population of gut organisms, there are approximately 500-1000 different species of bacteria, primarily depending on our age and diet. Whether we know it or not, we are the unwitting conductors of our biological symphony. The composition they are playing is positively influenced by us: 1) having had a vaginal birth; 2) being breastfed; 3) consuming a diverse, plant-based, high-fiber (40 grams) diet; 4) eating fermented foods; 5) drinking sufficient water (3 liters daily); 6) having adequate sleep (7-8 hours); 7) participating in regular positive social engagement and; 8) daily exercise (40 minutes). It is negatively impacted by cesarean birth, absence of breastfeeding, diets high in sugar and unhealthy fats, processed meat or excess red meat, alcohol, tobacco, overuse of antibiotics, chronic stress, a sedentary lifestyle, trauma, aging, loneliness and poor sleep.

1. Furness, J. B., Callaghan, B. P., Rivera, L. R., & Cho, H. J. (2014). The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: Integrated local and central control. In M. M. Akhtar, B. P. Callaghan, & E. G. Newgreen (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Vol. 817, pp. 39–71).

2. Armour JA, Murphy DA, Yuan BX, Macdonald S, Hopkins DA. Gross and microscopic anatomy of the human intrinsic cardiac nervous system. Anat Rec. 1997 Feb;247(2):289-98.

3. Azevedo, F. A. C., Carvalho, L. R. B., Grinberg, L. T., Farfel, J. M., Ferretti, R. E. L., Leite, R. E. P., Filho, W. J., Lent, R., & Herculano-Houzel, S. (2009). Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 513(5), 532–541.

4. Pakkenberg, B., & Gundersen, H. J. G. (1997). Neocortical neuron number in humans: Effect of sex and age. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 384(2), 312–320.

5. Carbia, C., Lannoy, S., Maurage, P., Lopez-Caneda, E., O’Riordan, K. J., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2021). A biological framework for emotional dysregulation in alcohol misuse: From gut to brain. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(4), 1098–1118.

6. Morais, L. H., Schreiber, H. L., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2020). The gut micro- biota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 19(4), 241–255.

7. Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506.

8. West KA, Yin X, Rutherford EM, Wee B, Choi J, Chrisman BS, Dunlap KL, Hannibal RL, Hartono W, Lin M, Raack E, Sabino K, Wu Y, Wall DP, David MM, Dabbagh K, DeSantis TZ, Iwai S. Multi-angle meta-analysis of the gut microbiome in Autism Spectrum Disorder: a step toward understanding patient subgroups. Sci Rep. 2022 Oct 11;12(1):17034.

9. Zhou, K., Baranova, A., Cao, H. et al. Gut microbiome and schizophrenia: insights from two-sample Mendelian randomization. Schizophr 10, 75 (2024).

10. Romano, S., Savva, G.M., Bedarf, J.R. et al. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. npj Parkinsons Dis. 7, 27 (2021).

11. Jin D-M, Morton JT, Bonneau R. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome uncovers shared and distinct microbial signatures between diseases. mSystems. 2024 Aug 20;9(8):e0029524.

12. Elmassry MM, Sugihara K, Chankhamjon P, Camacho FR, Wang S, Sugimoto Y, Chatterjee S, Chen LA, Kamada N, Donia MS. A meta-analysis of the gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease patients identifies disease-associated small molecules. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Feb 8:2024.02.07.579278.

13. Modesto Lowe V, Chaplin M, Sgambato D. Major depressive disorder and the gut microbiome: what is the link? Gen Psychiatr. 2023 Feb 17;36(1)

14. Chanda, D., & De, D. (2024). Meta-analysis reveals obesity associated gut microbial alteration patterns and reproducible contributors of functional shift. Gut Microbes, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2024.2304900

15. Jin D-M, Morton JT, Bonneau R. Meta-analysis of the human gut microbiome uncovers shared and distinct microbial signatures between diseases. mSystems. 2024 Aug 20;9(8):e0029524.

16. Pedersen HK, Gudmundsdottir V, Nielsen HB, Hyotylainen T, Nielsen T, Jensen BAH, Forslund K, Hildebrand F, Prifti E, Falony G, et al. 2016. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 535:376–381.

17. Ranjbar, M., Salehi, R., Haghjooy Javanmard, S. et al. The dysbiosis signature of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer-cause or consequences? A systematic review. Cancer Cell Int 21, 194 (2021).

18. Clarke SF, Murphy EF, O’Sullivan O, Lucey AJ, Humphreys M, Hogan A, Hayes P, O’Reilly M, Jeffery IB, Wood-Martin R. et al. Exercise and associated dietary extremes impact on gut microbial diversity. Gut. 2014;63(12):1913–1920.

19. Hu, C.; Shen, H. Microbes in Health and Disease: Human Gut Microbiota. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11354.

20. Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506.

21. Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141

22. Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: a role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:36–59. 10.1007/s13311-017-0585-0

23. Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002533.

24. Nguyen TT, Zhang X, Wu TC, Liu J, Le C, Tu XM, Knight R, Jeste DV. Association of Loneliness and Wisdom With Gut Microbial Diversity and Composition: An Exploratory Study. Front Psychiatry. 2021 Mar 25;12:648475.

25. Kim CS, Shin GE, Cheong Y, Shin JH, Shin DM, Chun WY. Experiencing social exclusion changes gut microbiota composition. Transl Psychiatry. 2022 Jun 17;12(1):254.