Emotional Suppression and Gut Feelings

Many of us learned to suppress our emotions in childhood, pushing down feelings of sadness, anger, fear, disgust, hurt, and even joy. When expressing emotions meant punishment, ridicule, being sent alone to our room, or being made wrong, it became adaptive to shut them down to avoid pain. We may have learned to not feel or show our emotions and internalized that they were dangerous, unacceptable, or a burden to others. We may have suppressed emotions to maintain approval and avoid criticism or rejection. With emotionally distant parents, children learn to ignore their emotions to sustain the relationship. In some families where parents or grandparents experienced war, famine, migration, oppression, or violence, emotional control may have been a survival mechanism—there was no space to express them, or you were encouraged to “be strong.” What were the emotions you suppressed as a child, and how did this protect you? Who did you have to become in that environment? What needs in you were not met because you were unable to express yourself? What is the “no” you wanted to say but couldn’t? How is emotional suppression showing up in your life now?

Emotional suppression cuts us off from the body and dulls our ability to feel. We dial down the awareness of visceral sensations from the gut, the heart, and our nervous system and learn to set feelings aside. Instead, we rely on logic, analysis, external rules or expectations, busyness, distractions, addictions, acquisitions, achievements, or prioritizing pleasing others instead of connecting to our body sensations, intuition, emotions, needs, and real wants. We look for validation from the outside rather than trusting ourselves. We abandon our inner authority and authenticity. Our gut is sending signals to the brain, but we are not getting the message. When this happens, our prefrontal cortex overrides these signals to perpetuate an outdated automatic, familiar response pattern (like saying yes when you mean no, or not speaking up when something is bothering you) that keeps emotions buried and unexpressed in an effort to stay safe. This is how we betray ourselves.

Stress and trauma influence both the brain and the gut flora. When the original trauma happened, if we did not speak to anyone about it, the emotions were suppressed. This creates inner conflict, confusion, and disconnection. Emotional expression is what helps to heal us, while emotional suppression makes us sick. Emotional and physical well-being can be enhanced by first connecting to the body, then sensing and expressing emotions in an environment of safety, as well as by tending to the ecosystem of the gut.

Activate Your Insula

The insula (or insular cortex) is an interoceptive hub that is part of your cerebral cortex, which is the brain’s outermost layer responsible for thought, language, and sensory processing. The insula’s role is complex—it allows you to feel your internal body state and links this with emotions, risk assessment, decision-making, sensory experience, empathy, and social connections. It connects “how you feel inside” with “what you choose to do,” creating alignment and coherence between body and mind. The insula senses, feels, smells, tastes, and responds to your gut, heart, and body, all at the same time. It detects temperature sensations, taste, smell, sensations on the skin, pain and pleasure, and is a center for empathy. We could accurately call it the brain’s seat of awareness or consciousness. It is responsible for the following staggering number of processes:

| Interoception (sensing body states)—notices internal bodily sensations (heartbeat, respiration, visceral feelings), primarily in the dorsal posterior insula | Controls speech—involved in speech motor networks |

| Subjective feelings, emotional awareness—integrates interoceptive signals into conscious feelings (how you “feel” emotionally), primarily in the anterior insula | Vestibular processing and balance contribute to your ‘righting reflex’ (ability to stand straight) and spatial orientation |

| Pain perception (nociception)—processes pain and the feelings associated with it | Somatosensory integration—integrates and localizes sensations of touch and temperature |

| Taste – plays a primary role in taste perception | Olfactory and gustatory links connect smell and taste to emotions like disgust |

| Autonomic regulation—plays a primary role in adjusting sympathetic/parasympathetic balance | Homeostatic drive and motivation – signals hunger, thirst and other drives that motivate behaviour |

| Generates anticipatory autonomic responses—prepares the body’s response before an expected stimulus or event, such as the sensory and emotional impact of touch | Self-awareness and metacognition—awareness of one’s own feelings |

| Cardiovascular control – monitors heart function | Integration of emotions over time—links different emotional moments to form a longer emotional context |

| Empathy and social emotions – responds to others’ emotional states (eg. empathy, disgust) | Integrates multimodal sensory information—combines visceral, somatic, gustatory and emotional inputs to make sense of something |

| Salience detection – prioritizes what is important to pay attention and respond to | Interoceptive predicting—computes a predicted response and compares it to the actual body state (predictive error signalling) |

| Network switching and cognitive coordination help to switch from default mode self-referencing to specific tasks | Cravings and addiction-related processes – responds to drug and food cues |

| Attention and anticipation—anticipates incoming stimuli and orients attention towards internal and external shifts | Emotional regulation and appraisal – appraises and adjusts emotional responses |

| Decision-making when there is uncertainty or risk – integrates body signals and emotions to make a choice | Preserves mental-emotional and neurological well-being—altered insular function or connectivity is implicated in anxiety, depression, addiction, schizophrenia, autism, stroke, and frontotemporal dementia |

| Integrates experience of orgasm—tracks internal body awareness, emotions and changes in the autonomic nervous system during orgasm (left anterior insula) |

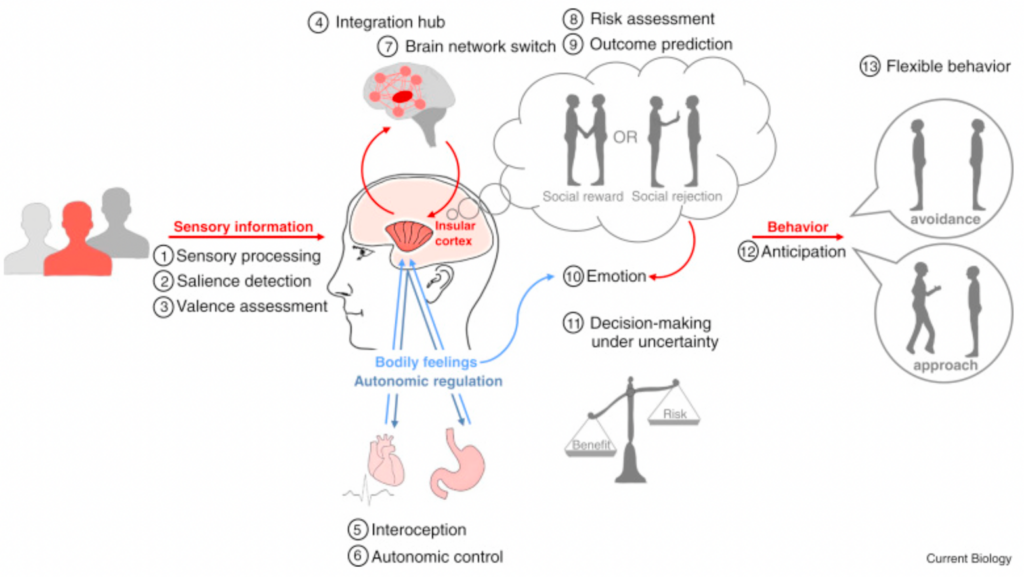

The diagram below outlines the insula’s response to a social encounter. Diagram is open access from: Gogolia, N. The insular cortex. Current Biology. Vol 27, Issue 12, R580–R586.

A model of how the insula functions during a social encounter. (1) The insular cortex receives multisensory information. In this example, it reacts to hearing or seeing people. (2) It processes the importance of incoming stimuli, that is, it responds more to the known (red silhouette) than to the unknown persons (grey silhouettes). (3) The insula assesses the valence of the stimulus, for example, whether this is a loved or dreaded person, by (4) integrating information from multiple brain systems, including emotional feelings for the person and cognitive information, for example, what is known about the person. The insula also perceives (5) bodily feelings and (6) contributes directly to physical reactions caused by the social encounter, e.g., an increase in heartbeat or the feeling of butterflies in the stomach. (7) Through its interactions with other large-scale brain networks, the insula (8) assesses the risk of an interaction by (9) predicting the possible outcomes, i.e., acceptance or rejection. (10) Bodily feelings as well as cognitive processes, e.g., imagination of the outcome, may cause emotions like pleasure or fear to interact. (11) The uncertainty of the other person’s reaction engages the insula in deciding what to do next. Upon a decision, the insula anticipates the outcome (12) and (13) influences the behavior of seeking or avoiding the contact.

The insula is also the gateway between our internal physiological and emotional experience and our motivational dopamine system. Through it, our body’s sensations dictate: 1) cravings; 2) motivation; 3) value-based decisions; 4) the effort we are willing to apply to an activity; 5) anticipation of reward; 6) vulnerability to addiction; 7) and our response to stress—whether to move towards or avoid a substance, person, place, or activity. It translates what we feel into what we want and what we will do to get it.

The insular cortex is divided into anterior and posterior regions, as well as right and left components. The posterior insula is involved in processing raw sensory signals from the body, such as temperature and touch, before these signals are consciously perceived in the anterior insula. The anterior insula plays an important role in the conscious awareness of bodily states and emotions, empathy, awareness of social behaviours, and decision-making. It integrates sensory information from the body, allowing us to experience feeling states such as emotions, hunger, thirst, pain and ecstatic states. Listed below are four primary regions of the insula, organized by function.

| Mid-posterior insula | Sensorimotor and interoceptive processing region, noting visceral sensations, autonomic signals, pain and body sensations. It connects to the primary and secondary somatomotor cortices. The primary somatomotor cortex initiates, controls and executes voluntary movement, while the secondary somatomotor cortex plans, sequences and prepares movement choices in response to our environment. It translates what we feel into how we choose to move. |

| Central insula | Olfactory and gustatory region (smell and taste). It is involved in integrating taste, nausea, visceral disgust, and the recognition of aversion. It maps how the inside of the body feels during unpleasant experiences. It translates body sensations such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiration and gut activity into emotions such as anxiety, calmness, excitement, hunger and cravings. It is implicated in drug, food and other compulsive addictions. It converts uncomfortable internal sensations into a motivational drive of “I need to fix this distressing feeling”. The central insula has projections to the ventral tegmental area, which is the primary generator of dopamine for the reward circuit. Interoceptive states (how you feel) can either increase or inhibit dopamine firing. “Surfing the urge” helps to inhibit a craving. |

| Anterior ventral insula | This is a social-emotional region, that connects to the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, which generates self-kindness, acceptance and compassion for others; decreases threat and stress signals; integrates body feelings with emotional meaning; supports social bonding and compassion; and dampens amygdala reactivity to foster emotional resilience.The anterior ventral insula brings awareness to “What I am experiencing right now.” It responds to disgust, nausea, emotional pain, shortness of breath, panic, moral disgust, betrayal, guilt and shame. It also allows us to feel empathy for others’ emotions, with compassion, tenderness and care, and to feel into their pain or distress (right insula). Activity in this region strongly predicts how intensely a person feels another person’s emotional or bodily state.It integrates interoceptive signals with emotional context, memories of similar experiences, meaning, and motivational relevance. It is in communication with the amygdala, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, ventral striatum (dopamine region) and anterior cingulate cortex. (The amygdala, ventromedial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex all have links to the hippocampus, or memory centre). It helps to transform emotional and interoceptive signals into urges and a need to act. This is the area we affect when we transform self-disgust and self-criticism into self-compassion. |

| Anterior dorsal insula | This is a cognitive region, connecting to the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, premotor cortex and the frontoparietal network. It transforms internal sensations and emotional signals into awareness of what we feel, as well as goal-directed behaviour and attention. It signals the urge to act, based on what we feel, and can be linked to compulsive urges and addiction. When it works well, we have emotional clarity, interoceptive accuracy and can make good decisions based on intuition. It helps us to shift our attention, focus under stress, suppress internal chatter and pay attention to important internal and external stimuli. When this area is impaired, we are easily distracted, have poor emotional awareness, or may experience anxiety with hypervigilance or PTSD hyperarousal. |

Reviewing the above regions, we see that together the areas of the insular cortex process what we feel, how we feel, what we want, how we feel towards others, and how we choose to act.

The right and left insula have different specializations.

| Function | Left Insula | Right Insula |

| Body Sensations | Processes objective representation of bodily states (e.g., recognizing a physiological change without deep subjective awareness). | More sensitive to subjective awareness of internal body states, such as heartbeat perception and pain intensity. |

| Emotions | More involved in positive emotions such as pleasure, affection, love, gratitude and cognitive control over emotions. Links body states to rational processing of emotions. | Specializes in intense emotions, particularly negative emotions (e.g., fear, disgust, anxiety). Helps in emotional arousal and visceral awareness. |

| Autonomic Nervous System | More linked to parasympathetic regulation (rest-and-digest), helping to regulate homeostasis and physiological balance. | Strongly linked to sympathetic activation (fight-or-flight response). Detects and processes changes in heart rate, breathing, and gut feelings. |

| Conscious Interoception | Helps process these sensations in a more cognitive and language-based manner, making sense of feelings. | Greater role in moment-to-moment awareness of visceral sensations (e.g., feeling butterflies in the stomach, tightness in the chest). |

| Pain Perception | More linked to sensory-discriminative aspects (where and how intense the pain is). | More linked to affective aspects of pain (how unpleasant pain feels). |

| Social and Empathy Processing | Contributes to perspective-taking and cognitive evaluation of others’ emotions. | Helps perceive others’ pain and emotions at a visceral level (i.e., empathic resonance). |

Lateral Specialization

To summarize, the right insula is dominant in self-awareness of body signals and emotions and activated during practices such as mindfulness, meditation, and yoga, and through pausing to pay attention to sensations and emotions. The right insula has been described as providing the glue between different capacities of self-consciousness, including interoception, proprioception, and being able to recognize the boundaries of one’s body. The right insula is also involved with processing mental thoughts about oneself.

A right insula dysfunction can be linked to anxiety, PTSD, and panic disorders, where heightened interoception can lead to exaggerated bodily awareness coupled with emotional states such as fear, disgust, pain shame, guilt, and anxiety, paired with a sympathetic response signifying tension.

The left insula helps contextualize and interpret these sensations, integrating them with language and cognitive understanding. The left insula registers positive emotions related to warmth, connection, calmness, and reward, associated with parasympathetic dominance. A left insula dysfunction is linked to alexithymia (difficulty naming emotions) and challenges with emotional regulation.

The right insula is more dominant for subjective interoceptive awareness, linking body sensations to emotional experiences, while the left insula helps process and cognitively interpret these sensations. Both sides are essential for self-awareness, emotional regulation, and well-being.

How Trauma Affects the Insula

In traumatized people, brain activation studies reveal either abnormal activation or deactivation of the insula. Childhood trauma and emotional suppression cause our nervous systems to go into either a hyper-aroused state of sympathetic dominance, commonly known as fight/flight, or a hypo-aroused state of shutdown, freeze, or collapse—a parasympathetic response of the dorsal vagus nerve. These responses can either distort gut feelings or make them inaccessible.

As a result, trauma survivors either feel chronically unsafe in their bodies when alerted to warning signs from their gut or other body parts or may numb or shut down body awareness as a protective mechanism. This can lead to dissociation, “not feeling alive,” or an inability to sense emotions and internal states, and causes difficulties such as alexithymia (trouble naming feelings), emotional numbing, difficulty experiencing pleasure, inability to regulate physiological states (e.g., arousal, stress), or pervasive hypervigilance—even when no external danger is present. Trauma and chronic emotional suppression overactivate or decrease the activity of the insula, which makes it difficult to know what we really feel. We shut down the brain areas responsible for registering the magnificent array of sensations and emotions that form the base of our self-awareness, our sense of who we are, and what it means to be human. Trauma causes us to lose touch with our body, emotions, choices, and sense of self.

The amygdala is an area of the brain that influences the anterior insula and interoception. The amygdala’s role is to detect danger or threat, like a smoke alarm. It is activated when something is frightening, painful, unpredictable, socially threatening, or emotionally intense. The amygdala is overactive in individuals who have experienced trauma or have been diagnosed with PTSD. When the amygdala is activated, it sends strong signals to the anterior insula that cause the insula to scan for danger by detecting angry or fearful faces, a threatening tone of voice, or internal changes in heart rate, muscle tension, pain, breathing patterns, and gut feelings. In other words, when the amygdala is turned on, the insula prioritizes and amplifies sensations that may predict harm. This means that the insula will over-detect signals of threat and under-detect calming or safe cues. The anterior insula then generates emotional states to match the interpretation of the cue—such as anxiety, fear, terror, urgency, anger, or caution. Then our prefrontal cortex will create a belief that matches the emotional tone, which then perpetuates the emotional state. Like a caged animal, we get caught in a mental loop from which it is difficult to escape.

When the insular cortex is atrophied or impaired, we disconnect from ourselves—we don’t sense what we feel or want. We may be oblivious to our real needs and thus cater to others’ needs as a compensation. If we can’t feel the body, then our immune system doesn’t pick up when there is something in the body that needs to be addressed. We lose touch with ourselves due to this lack of communication between body and brain. Chronic mental and physical illness, autoimmune disease, cancer, dementia, addiction, eating disorders, and disconnection can be the result because our monitoring system isn’t working. A 2022 study of 626 individuals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, PTSD, anxiety, eating disorders, or substance use disorders found that these people had disrupted activity in the left dorsal mid-insula, when compared to 610 healthy control subjects.

The relaying of information from the gut to the insula begins with signals picked up by the vagus nerve, routed through the brainstem and thalamus, before reaching the insula. Along with other sensory stimuli from the rest of the body and the heart, the insula receives information about gut sensations, pain, inflammation and the composition and activity of the gut microbiome. It prioritizes signals that are emotionally important, rewarding, threatening, painful, or relevant to a goal.

26. Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017 Jul;34(4):300-306.

27. Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017 Jul;34(4):300-306.

28. Craig AD. How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Jan;10(1):59-70.

30. Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017 Jul;34(4):300-306.

31. Pugnaghi M, Meletti S, Castana L, et al. Features of somatosensory manifestations induced by intracranial electrical stimulations of the human insula. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:2049–2058.

32. Naidich TP, Kang E, Fatterpekar GM, Delman BN, Gultekin SH, Wolfe D, Ortiz O, Yousry I, Weismann M, Yousry TA. The insula: anatomic study and MR imaging display at 1.5 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004 Feb;25(2):222-32.

33. Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017 Jul;34(4):300-306.

34. Naidich TP, Kang E, Fatterpekar GM, Delman BN, Gultekin SH, Wolfe D, Ortiz O, Yousry I, Weismann M, Yousry TA. The insula: anatomic study and MR imaging display at 1.5 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004 Feb;25(2):222-32.

35. Kathryn L. Lovero, Alan N. Simmons, Jennifer L. Aron, Martin P. Paulus. Anterior insular cortex anticipates impending stimulus significance. NeuroImage, Volume 45, Issue 3, 2009. pages 976-983,

36. Tayah T, Savard M, Desbiens R, Nguyen DK. Ictal bradycardia and asystole in an adult with a focal left insular lesion. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1885–1887.

37. Oppenheimer SM, Gelb A, Girvin JP, Hachinski VC. Cardiovascular effects of human insular cortex stimulation. Neurology. 1992;42:1727–1732.

38. Craig AD. Emotional moments across time: a possible neural basis for time perception in the anterior insula. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 Jul 12;364(1525):1933-42.

39. Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and Function of the Human Insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017 Jul;34(4):300-306.

40. Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA. Three systems of insular functional connectivity identified with cluster analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2011 Jul;21(7):1498-506.

41. Kathryn L. Lovero, Alan N. Simmons, Jennifer L. Aron, Martin P. Paulus. Anterior insular cortex anticipates impending stimulus significance. NeuroImage, Volume 45, Issue 3. 2009. Pages 976-983.

42. Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA. Three systems of insular functional connectivity identified with cluster analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2011 Jul;21(7):1498-506.

43. Namkung H, Kim SH, Sawa A. The Insula: An Underestimated Brain Area in Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, and Neurology. Trends Neurosci. 2017 Apr;40(4):200-207. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.02.002. Epub 2017 Mar 15.

44. Kathryn L. Lovero, Alan N. Simmons, Jennifer L. Aron, Martin P. Paulus. Anterior insular cortex anticipates impending stimulus significance. NeuroImage, Volume 45, Issue 3, 2009, Pages 976-983.

45. Craig AD. How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Jan;10(1):59-70.

46. Namkung H, Kim SH, Sawa A. The Insula: An Underestimated Brain Area in Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, and Neurology. Trends Neurosci. 2017 Apr;40(4):200-207.

47. Ortigue S, Grafton ST, Bianchi-Demicheli F. Correlation between insula activation and self-reported quality of orgasm in women. Neuroimage. 2007 Aug 15;37(2):551-60.

48. Funk AT, Hassan AA, Waugh JL. In Humans, Insulo-striate Structural Connectivity is Largely Biased Toward Either Striosome-like or Matrix-like Striatal Compartments. Neurosci Insights. 2024 Sep 10;19:26331055241268079.

49. Eduardo Hernández-Ortiz, Jorge Luis-Islas, Fatuel Tecuapetla, Ranier Gutierrez, Federico Bermúdez-Rattoni. Top-down circuitry from the anterior insular cortex to VTA dopamine neurons modulates reward-related memory. Cell Reports, Volume 42, Issue 11, 2023, 113365, ISSN 2211-1247.

50. Haruki Y, Ogawa K. Role of anatomical insular subdivisions in interoception: Interoceptive attention and accuracy have dissociable substrates. Eur J Neurosci. 2021 Apr;53(8):2669-2680.

51. Chen WG, Schloesser D, Arensdorf AM, Simmons JM, Cui C, Valentino R, Gnadt JW, Nielsen L, Hillaire-Clarke CS, Spruance V, Horowitz TS, Vallejo YF, Langevin HM. The Emerging Science of Interoception: Sensing, Integrating, Interpreting, and Regulating Signals within the Self. Trends Neurosci. 2021 Jan;44(1):3-16.

52. Gschwind M, Picard F. Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures: A Glimpse into the Multiple Roles of the Insula. Front Behav Neurosci. 2016 Feb 17;10:21. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00021.

53. Cai W, Menon V. Heterogeneity of human insular cortex: five principles of functional organization across multiple cognitive domains. Brain Struct Funct. 2025 Oct 23;230(8):161.

54. Zahn, R., et al. (2009). The neural basis of moral sentiment. PNAS, 106(32), 14052–14057.

55. Rolls, E. T. (2023). The anterior insula, social emotion, and human social behavior. Cortex, 168, 149–166.

56. Sescousse, G., et al. (2023). Insular–striatal circuits in human motivation. Nature Neuroscience, 26(1), 112–123.

57. Gu, X., & FitzGerald, T. H. (2014). Interoceptive inference: A Bayesian framework for understanding the anterior insula. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 419–429.

58. Gu, X., & FitzGerald, T. H. (2014). Interoceptive inference: A Bayesian framework for understanding the anterior insula. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 419–429.

59. Scalabrini A, Wolman A, Northoff G. The Self and Its Right Insula-Differential Topography and Dynamic of Right vs. Left Insula. Brain Sci. 2021 Oct 2;11(10):1312. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11101312. PMID: 34679377; PMCID: PMC8533814.

60. Lee D, Lee JE, Lee J, Kim C, Jung YC. Insular activation and functional connectivity in firefighters with post-traumatic stress disorder. BJPsych Open. 2022 Mar 15;8(2):e69.

61. Istvan Molnar-Szakacs, Lucina Q. Uddin. Anterior insula as a gatekeeper of executive control, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 139, 2022, 104736.

62. Meng L, Jiang J, Jin C, Liu J, Zhao Y, Wang W, Li K, Gong Q. Trauma-specific Grey Matter Alterations in PTSD. Sci Rep. 2016 Sep 21;6:33748.

63. Kleshchova O, Rieder JK, Grinband J, Weierich MR. Resting amygdala connectivity and basal sympathetic tone as markers of chronic hypervigilance. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 Apr;102:68-78.

64. Nord CL, Lawson RP, Dalgleish T. Disrupted Dorsal Mid-Insula Activation During Interoception Across Psychiatric Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 1;178(8):761-770